A Last Word

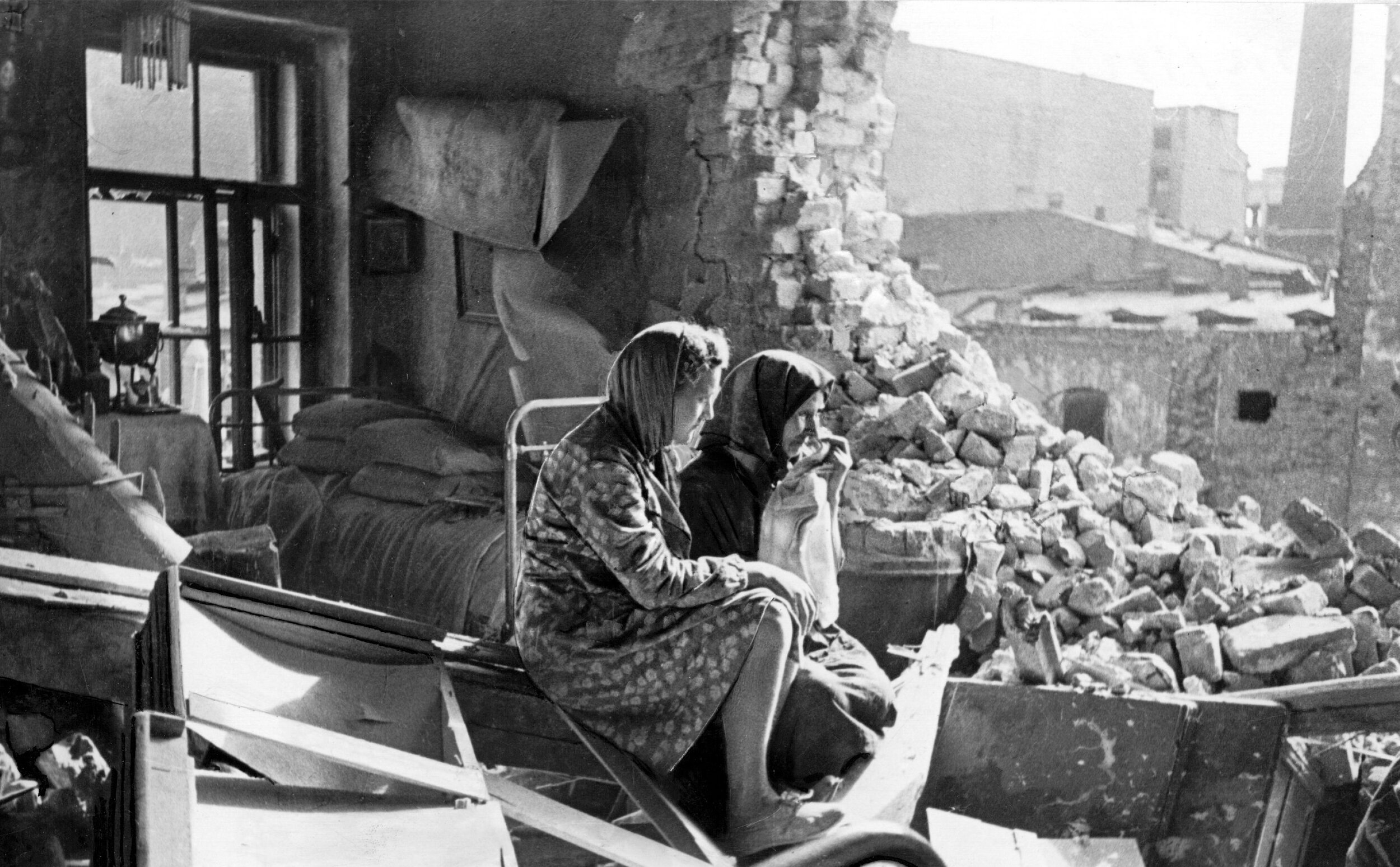

This picture illustrates in a woefully small way what the people of Russia went through in the last century, one such horror being this Great Patriotic War - World War II to us - that cost some 20 million of them their lives.The once beautiful city of St. Petersburg became Leningrad after Czar Nicholas II was overthrown in 1917 and it was renamed. Then, just 25 years after that, this 'Leningrad' became.... a graveyard: Hitler's Nazi troops laid siege to the city in early September of 1941 and held it by the throat until the end of January in 1944.For those 900 days, it was surrounded. Supplies of coal and oil were cut off. Then, because the siege began in the autumn, the cold weather began bearing down, bringing nights below freezing as early as in October.As winter set in for real, and with no heat source, the pipes all froze.There was almost no food. Potable water was scarce.And then there were the daily shellings.

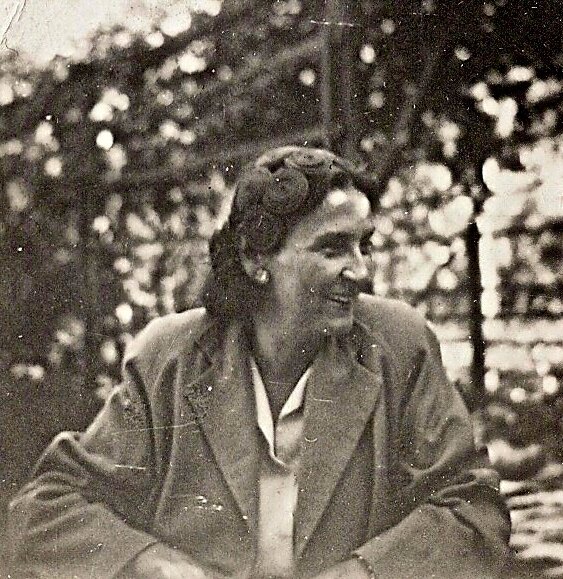

This picture illustrates in a woefully small way what the people of Russia went through in the last century, one such horror being this Great Patriotic War - World War II to us - that cost some 20 million of them their lives.The once beautiful city of St. Petersburg became Leningrad after Czar Nicholas II was overthrown in 1917 and it was renamed. Then, just 25 years after that, this 'Leningrad' became.... a graveyard: Hitler's Nazi troops laid siege to the city in early September of 1941 and held it by the throat until the end of January in 1944.For those 900 days, it was surrounded. Supplies of coal and oil were cut off. Then, because the siege began in the autumn, the cold weather began bearing down, bringing nights below freezing as early as in October.As winter set in for real, and with no heat source, the pipes all froze.There was almost no food. Potable water was scarce.And then there were the daily shellings. According to an account by someone who lived through this unimaginable time in Leningrad, the unlucky souls who collapsed in the streets in the morning were just a few more snow-covered mounds by night. Even after the ground thawed enough to allow for burial, the dead were interred without coffins, their families standing by hollow-eyed and in silence. One witness to this history reports that "on the whole men collapsed more easily than women, and at first the death-rate was highest among men." Was that because women have more adipose tissue you wonder? He goes on: "However, the women felt the after-effects more seriously than the men. They stopped menstruating and many died in the spring, when the worst was already over."People no longer smiled, it was reported. The city's four-legged creatures began to disappear, killed and eaten, even the rats. By some silent accord it was agreed that one would not speak of 'real' food. In the end, by the time the siege was lifted ,fully a million of the city’s residents had died.It is hard for us Americans to even imagine this kind of suffering. I have learned from reading my own family's diaries and letters that during that 900-day period here in the States my mother was pursuing her life as a hale and energetic woman running the family business, ordering all the food, hiring and managing staff and maintaining its 120-acre grounds. Her 70-something father was, for his part, still happily working as an attorney and a district court judge and keeping a journal in which he marked the comings and goings of the birds he looked for on his long strolling walks.It's true that there was some privation stateside: gasoline was rationed, as were shoes. Butter also 'went to war' so folks had to make do with oleo.But as far as I have been able to learn, people didn't go hungry ,and women didn't stopped menstruating because their bodies had shut down all functions not necessary for survival. In fact mother and my aunt were living so far from survival mode that they were still delivering babies well into their 40s.Here is my mom now, pregnant with her first child a few months after Victory over Japan Day in August of 1945. (VE, or Victory in Europe day had of course occurred the previous April.) The only thing World War II did to her was to deliver to her doorstep the blue-eyed coast Guard officer who would one day become my father.

According to an account by someone who lived through this unimaginable time in Leningrad, the unlucky souls who collapsed in the streets in the morning were just a few more snow-covered mounds by night. Even after the ground thawed enough to allow for burial, the dead were interred without coffins, their families standing by hollow-eyed and in silence. One witness to this history reports that "on the whole men collapsed more easily than women, and at first the death-rate was highest among men." Was that because women have more adipose tissue you wonder? He goes on: "However, the women felt the after-effects more seriously than the men. They stopped menstruating and many died in the spring, when the worst was already over."People no longer smiled, it was reported. The city's four-legged creatures began to disappear, killed and eaten, even the rats. By some silent accord it was agreed that one would not speak of 'real' food. In the end, by the time the siege was lifted ,fully a million of the city’s residents had died.It is hard for us Americans to even imagine this kind of suffering. I have learned from reading my own family's diaries and letters that during that 900-day period here in the States my mother was pursuing her life as a hale and energetic woman running the family business, ordering all the food, hiring and managing staff and maintaining its 120-acre grounds. Her 70-something father was, for his part, still happily working as an attorney and a district court judge and keeping a journal in which he marked the comings and goings of the birds he looked for on his long strolling walks.It's true that there was some privation stateside: gasoline was rationed, as were shoes. Butter also 'went to war' so folks had to make do with oleo.But as far as I have been able to learn, people didn't go hungry ,and women didn't stopped menstruating because their bodies had shut down all functions not necessary for survival. In fact mother and my aunt were living so far from survival mode that they were still delivering babies well into their 40s.Here is my mom now, pregnant with her first child a few months after Victory over Japan Day in August of 1945. (VE, or Victory in Europe day had of course occurred the previous April.) The only thing World War II did to her was to deliver to her doorstep the blue-eyed coast Guard officer who would one day become my father. I've been home from Russia for more than two months now but I still can't entirely process what I've learned about its history. There was this war, and then there was rule of Stalin who with his purges and the famines his decrees caused brought about the deaths of another 20 million people - and 20 is the conservative estimate. Then there were the grim years under Khrushchev, and Andropov, Brezhnev and Chernenko. Then came Gorbachev in the 80s with his talk of Perestroika and Glasnost but all that ended with his resignation when first Yeltsin and finally Putin took up the reins of authority.Now, those Russians who remember the Soviet era look back in a kind of sad wonderment at all that has changed in their country and in their lives.“The Soviet regime?" recalled one in Secondhand Time, The Last of The Soviets, by Svetlana Alexievich, the 2015 winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature. “It wasn’t ideal, but it was better than what we have today. Worthier. Overall, I was satisfied with socialism: No one was excessively rich or poor; there were no bums or abandoned children. Bela Shayevich who was Secondhand Time ‘s English translator, called the book a kind of update of 19th-century Russian literature for the 21st century. “People read Russian novels not for the happy endings because there is great catharsis in great pain and then something that is sublime.” I get that.But then what happened? The abandonment. The Save Your Own Life phase of Russian living that arrived almost overnight. It had a devastating effect on the people:"Imagine working that hard, your whole life, only to end up with nothing. All of it took the ground out from underneath people, their world was shattered; they still haven’t recovered, they couldn’t assimilate into the drastically new reality. When they started selling salami at the privately owned stores, all of us ran over to ogle it. And that was when we saw the prices! This was how capitalism came into our lives... Wild, inexplicable avarice took hold of everyone. The smell of money filled the air. Big money. And absolute freedom—no Party, no government. Everyone wanted to make some dough, and those who didn’t know how envied those who did.""I get indignant whenever people start talking about Marxism with disdain and a knowing smirk," says another. "It’s a great teaching, and it will outlive all persecution, and our Soviet misfortune, too. It wasn't just about labor camps, and informants, and the Iron Curtain, it's a bright, just world, where everything is shared, the weak are pitied, and compassion rules. Instead of grabbing everything you can, you feel for others. "I find this last the most touching part of all: the feeling we all have about what our country could be. I think of a section from Reg Saner's short poem "Green Feathers" which expresses our universal longing:

I've been home from Russia for more than two months now but I still can't entirely process what I've learned about its history. There was this war, and then there was rule of Stalin who with his purges and the famines his decrees caused brought about the deaths of another 20 million people - and 20 is the conservative estimate. Then there were the grim years under Khrushchev, and Andropov, Brezhnev and Chernenko. Then came Gorbachev in the 80s with his talk of Perestroika and Glasnost but all that ended with his resignation when first Yeltsin and finally Putin took up the reins of authority.Now, those Russians who remember the Soviet era look back in a kind of sad wonderment at all that has changed in their country and in their lives.“The Soviet regime?" recalled one in Secondhand Time, The Last of The Soviets, by Svetlana Alexievich, the 2015 winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature. “It wasn’t ideal, but it was better than what we have today. Worthier. Overall, I was satisfied with socialism: No one was excessively rich or poor; there were no bums or abandoned children. Bela Shayevich who was Secondhand Time ‘s English translator, called the book a kind of update of 19th-century Russian literature for the 21st century. “People read Russian novels not for the happy endings because there is great catharsis in great pain and then something that is sublime.” I get that.But then what happened? The abandonment. The Save Your Own Life phase of Russian living that arrived almost overnight. It had a devastating effect on the people:"Imagine working that hard, your whole life, only to end up with nothing. All of it took the ground out from underneath people, their world was shattered; they still haven’t recovered, they couldn’t assimilate into the drastically new reality. When they started selling salami at the privately owned stores, all of us ran over to ogle it. And that was when we saw the prices! This was how capitalism came into our lives... Wild, inexplicable avarice took hold of everyone. The smell of money filled the air. Big money. And absolute freedom—no Party, no government. Everyone wanted to make some dough, and those who didn’t know how envied those who did.""I get indignant whenever people start talking about Marxism with disdain and a knowing smirk," says another. "It’s a great teaching, and it will outlive all persecution, and our Soviet misfortune, too. It wasn't just about labor camps, and informants, and the Iron Curtain, it's a bright, just world, where everything is shared, the weak are pitied, and compassion rules. Instead of grabbing everything you can, you feel for others. "I find this last the most touching part of all: the feeling we all have about what our country could be. I think of a section from Reg Saner's short poem "Green Feathers" which expresses our universal longing:

In the early air we keep trying to catch sight of something lost up ahead,

A moment when the light seems to have seen us exactly as we wish we were.

Like a heap of green feathers poised on the rim of a cliff?

Like a sure thing that hasn’t quite happened?

Like a marvelous idea that won’t work?

Routinely amazing -

How moist tufts, half mud, keep supposing almost nothing is hopeless.

How the bluest potato grew eyes on faith the light would be there.

And it was.

We all still look for that light and we pray, like the small and buried potato, that it will one day reveal itself to our sight.